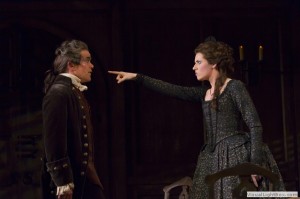

Adam Green, Maggie Lacey, and Naomi O’Connell in THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO at the McCarter Theatre Center through May 4. – Photo by T. Charles Erickson

What was good got much, much better. THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO, the second of the two FIGARO PLAYS on offer at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton makes up and then some for any shortcomings found in the first. This exuberant production is high-energy and infectious from the very beginning, and it continues to dazzle through its three-plus hours that fly by all too quickly.

Where Adam Green’s Figaro of THE BARBER OF SEVILLE seemed rather lackluster and introspective, here, he’s a dynamo who whirrs even when standing still. He’s always thinking, even when he’s incorrect, and the result is like watching a tightly wound spring that may explode at any second, and he maintains this tension throughout the entire evening and then overcome a huge monologue Beaumarchais has given him near the very end of the play which he does with ease.

Indeed, the entire cast is to be commended in superlatives as they whisk the audience along in this delightful melee.

Once again, if you’re a fan of the opera, you’ll know the story. Figaro (Green) is back in the employ of Count Almaviva (Neal Bledsoe) who is now married to his quest of the first play, Rosine (Naomi O’Connell), and Figaro is about to be married to his love (Suzanne) Maggie Lacey. The only problem is that the Count is infatuated with Suzanne and wants to reestablish a custom he previously abolished, droit de seigneur or the right of the master that allows him to bed a servant’s wife on her wedding night. Neither Figaro, Suzanne, nor Rosine is happy about this, but Almaviva seems to have decided that he has to do it although he is not truly happy about it himself. He has once again enlisted the aid of Bazile (Cameron Folmer) to act as his go-between, but Bazile has his mind on other issues.

The complications in this play are many, and they add a host of new and hilarious complications. Since Almaviva wants Suzanne as his mistress, he is pleased that Marceline (Jeanne Paulsen) who is Dr. Bartolo’s (Derek Smith) housekeeper has a promissory note that states that Figaro must marry her. Almaviva hopes to push this issue in court, but he is somewhat obstructed by Bazile who is in love with Marceline.

Further complications come from one of Almaviva’s pages Cherubin (Magan Wiles) who is also the godson of Rosine. Cherubin is in love with anything wearing a dress, and he has fallen from favor with the Count because he has been found canoodling with the shepherdess Fanchette (Betsy Hogg) who is also a target of the Count’s affections. Cherubin is also in love with Rosine and even states that he thinks making love to Marceline would be an excellent adventure. How all of these characters try to get the better of each other through trickery and disguises and the secrets one discovers along the way makes this one wonderful roller-coaster ride.

The focus has shifted from Rosine and Almaviva as the lovers to Figaro and Suzanne who are now those in trouble and needing help, and Lacey’s Suzanne is every bit a match for Figaro’s wiles. Lacey is simply superb. She is charming and has a presence that draws the audience to her. When she is on stage with O’Connell who delivers another stellar performance, it is bliss. Magan Wiles’ Cherubin is a glorious study of pained adolescence. She captures the changeability of youth perfectly and is at once pitiable and annoying (in a good way).

Neal Bledsoe seems much more at home in this Almaviva skin. His man of action who seems torn between two minds is a much more positive presence on the stage. The man is still a major heel, but he’s a heel one can understand and possibly find sympathy for. Derek Smith is, once again, wonderful. I don’t need to add any more to that. I’ll happily go to see him in anything if these two plays are any indication of his abilities.

The plot twists are numerous and the evening speeds by all too quickly. It’s been a long time since I’ve enjoyed a night in the theatre like this.

Charles Corcoran’s sets are more pleasing to the eye here. Granted, there are more scenes and locations in this play than there were in the first, but here, the dull walls are given variety by windows allowing more light and patches of blue to show through. There is a lighter, brighter feel to these settings. Joan Arhelger’s lights offer more variety here as well and are generally better suited to the lightness of the script. Only in the night scene near the end do they go through some tortured changes and leave most of the cast in half-light and shadow.

There is a wonderful variety in the costumes by Camille Assaf here; no longer is everything dull. Even though were still mostly in a palate of earth-tones, there are some rich hues that offer some relief from the brown/gray of the sets. Assaf’s designs are once again nicely realized, and this wider and brighter palate server them well.

Stephen Wadsworth’s adaptation and direction are once again delightful as well. The pace is perfect with the audience being allowed to pause and reflect when necessary and pushing through the comedic moments, heaping them on one another to glorious effect.

I am truly sorry for gushing, but this production so richly deserves it.

Another aspect of this script that I found particularly interesting was its timelessness and appropriateness for today. Marceline, who had little to do in the first play but who is pivotal in this one, delivers a telling monologue about the place of women in society. She bemoans the fact that women are subjected to a society that does not fully value them, that looks on them as commodities who are worth less than men. I found this to be highly topical concerning the statements currently being made by some politicians concerning equal pay and opportunities for women today. She also rails against her being even more powerless because she has no money and is at the mercy of the rich who own and control most of society. This too is all too poignant when compared to the world some 250 years later.

It must be noted that Jeanne Paulsen is brilliant as Marceline. Her monologue is delivered honestly and directly, and one can feel her pain as she explains her plight. Paulsen is solid throughout the night, but she truly shines here.

I wanted to brilliantly weave some of Wadsworth’s translated lines through this review, but I thought it might be more fun to let them live on their own. That way, those of you who go to see this show, and you should go to see this show – both shows, would also have the joy to see from whence they come.

Here are a few of my favorites (I’m sorry if any are incorrect. I was writing as fast as I could, and it was dark, after all.):

“What mortal abandoned by heaven and womankind would want you?”

“If I could get her without a struggle, I’d want her even less.”

“I won’t speak to my character, but I’m definitely better than my reputation.”

“Of course I tell him everything except what I don’t tell him.”

“I should have known that you were my mother when I started borrowing money from you.”

“If you don’t stand up to them, you are utterly dependent to them.”

…And my favorite,

“The only good thing about a theatre is that you can take a nap in it.”

Like several other Wadsworth translations/adaptations, I am sure that there will be more chances to see THE FIGARO PLAYS as it is produced in other regional theatres, but if you are in the Princeton area, by all means try to see both of these plays. Even though THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO is a more developed and complex story, the two together are a remarkable theatre-going package. There is a reason the works of people like Beaumarchais survive. There is a timelessness and a universality that reaches across decades, and they are just as fresh and alive each time they are performed. Together at The McCarter Theatre Center, they are simply a joyous romp.

THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO continues in repertory with THE BARBER OF SEVILLE through May 4 in the Matthews Theatre at the McCarter Theatre Center, 91 University Place in Princeton, NJ 08540. For information, call (609) 258-2787 or visit their website at http://www.mccarter.org.

Derek Smith as Bartolo and Naomi O’Connell as Rosine in THE BARBER OF SEVILLE at the McCarter Theatre Center – photo by T. Charles Erickson

Sometimes, while watching a play one has never seen before, it may seem wonderfully familiar. The story may be different, but there is that strange feeling that these characters come from somewhere else. In retrospect, this is not a bad thing; it just means that a viewer has a history with the theatre on which to base his or her experience.

This was the case during THE BARBER OF SEVILLE, the first of THE FIGARO PLAYS being presented in repertory at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, NJ through May 4. The second, THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO, will be forthcoming. Stephen Wadsworth, who translated, adapted, and directed these pieces, is no stranger to McCarter audiences as he delivered delightful productions of forgotten plays by Marivaux and Goldoni here in the 1990s. This time, it’s the works of Pierre Beaumarchais which are far better known in their operatic forms. Beaumarchais was a French watchmaker who elevated the erratic timepieces of the day to reliable works of art (even fashioning the first watch set into a ring) and hoped for a political post in Spain. When that did not come, he began writing plays, and they were very popular plays at that.

If you are familiar with the opera, then you know the story. The wily Figaro (Adam Green) helps his former master, Count Almaviva (Neal Bledsoe) win the woman he has followed throughout Europe, Rosine (Naomi O’Connell). To do that, Figaro confounds Rosine’s guardian Bartolo (Derek Smith) and his toady Don Bazile (Cameron Folmer). Bartolo is planning to marry the much younger Rosine in order to secure her fortune for himself.

Besides the storyline, the familiar part of this comes with the characters. Beaumarchais was writing at a transitional time in the mid-eighteenth century after the Restoration and Classical periods and before the Romantic, but he still looked to theatre history for the characters that people these scripts. The plays of this time seem to rely heavily on satire and social commentary, and Beaumarchais used characters that come directly from the stock characters of the commedia del’arte of the sixteenth century to act out his story.

The agile wit, Arlecchino, is Figaro. Here, the Count and Rosine are characters that were known by many names but came under the heading of Inamorato, the young people in love who always seem to have the problem that needs to be fixed. Bartolo is the Venetian merchant Pantalone who is rich, mean, and miserly. Rounding out the main cast is Bazile whose counterpart would be Il Dottore (the doctor) who is a learned man who is full of himself and easily swayed from his purpose by money. They’re all there plus a few more, and it makes it very easy to follow their exploits because they are so familiar.

Although Adam Green seemed a bit low on energy and flair for Figaro on opening night, he still turned in a serviceable job. Because of the type of character he plays, one expects a far more robust performance. Not overly loud and large, but Figaro is a schemer who is always thinking. Here, he is affable but too laid back to really get involved. He is a complainer, not a doer.

Neal Bledsoe had a slow start on opening night, but he made up for it as the play progressed. His Count Almaviva is dashing and a bit daunted which gives audiences a character for whom they should be rooting which is necessary. This dynamic will shift in THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO.

My two favorite performances of the evening were delivered by Naomi O’Connell as the charming Rosine whose nicely delineated moments of happiness, despair, and confusion were delightful to watch and Derek Smith’s Bartolo. Bartolo always seems to be on the edge of a nervous breakdown, and his wonderfully stylized mannerisms and delivery support that characterization perfectly. Smith’s Bartolo is an amiable curmudgeon who delights audiences with his complaints like “If people didn’t drop things, no one would be talking about gravity.” During the evening, I often found myself wishing that Green had channeled some of Smith’s energies.

The physical production for this play is quite nice although the set by Charles Corcoran is rather monochromatic and drably painted. Regardless of the validity of the color choices, from the audience, it gives little visual variety and is a bit somber. The colors wash out under the theatre-lighting to a flat beige and gray. The two-tiered design itself is impressive, and it gives the characters ample playing room.

Camille Assaf’s costumes are nicely detailed and appropriate, and Joan Arhelger’s lighting is serviceable but offers no special notes. Everything was just nicely designed; it just seems as though there was a conscious effort to underplay the result which gives the production no sparkle. I’m not saying that there should be bright colors and lights, just that there should be some focal points to ease the flatness of the visual, some special visuals to go with some special moments being offered on stage.

Wadsworth has given audiences another gem in this translation/adaptation. These characters have survived for over two hundred years because they are special, and with lines that read, “Public service and private gain at the same time – it’s morally unimpeachable,” one can see why. Their essence lives on. Wadsworth’s direction is generally well paced after a slow opening, and he allows the characters time to grow and mature throughout the production. He obviously trusts the material and allows things to happen rather than forcing them on his audiences which is refreshing.

My quibbles with the production and a few of the performances are just that: quibbles. They are minor in the grand scheme of the evening, and this production, on the whole, is wonderful. THE BARBER OF SEVILLE at the McCarter Theatre is a well presented, silly bit of charming entertainment, and it is a fabulous reminder of how enjoyable a well-crafted play can be.

THE BARBER OF SEVILLE continues in repertory with THE MARRIAGE OF FIGARO through May 4 in the Matthews Theatre at the McCarter Theatre Center, 91 University Place in Princeton, NJ 08540. For information, call (609) 258-2787 or visit their website at http://www.mccarter.org.

Adam Green, Derek Smith, and Neal Bledsoe in THE BARBER OF SEVILLE at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, NJ. – photo by T. Charles Erickson

It has taken me a while to sit down to write this review, but I am not sure as to why this has happened. I think it may be that it was such a disappointing experience that I didn’t want to think about it. An anonymous writer once penned, “Absence makes the heart grow fonder,” but in this case, it didn’t. Even though it’s been quite a while since I saw the performance, I’m still miffed at this production by the Fiasco Theatre Company which appeared at McCarter Theatre’s Berlind Theatre from May 3 to June 9. It was a “new take” on Sondheim’s incredible musical, and whenever I see terms like “a new take,” “reimagined,” or “updated,” I immediately get suspicious.

INTO THE WOODS is another of “those” musicals; people either love it or hate this show that has been on Broadway three times chalking up a total of 1044 performances and garnering five Tony Awards and a host of other awards for those outings. It is one of Sondheim’s most clever shows lyrically, and the clarity of the music and lyrics is essential to the success of the piece.

I have been fortunate in seeing this show done many times. The original Broadway production was charmingly set with most of the woods suggested by a series of drops – very simply done. The original London production was much darker with an almost gothic feel to the dark and foreboding woods and a huge cuckoo clock presiding over all. An edge was added to this production which made it less accessible. A pared-down, but successful production was mounted by students at The Royal Academy of Music in the 1990’s because they preserved the integrity of the music, lyrics, and book, and the most recent Broadway outing in 2002 which seemed unfocused for some reason. There have been touring companies, as well as many regional companies that have met with various levels of success. However, all of these have tried to do just service to the material.

However, here, the show was unmercifully hacked down to a cast of eleven from nineteen as written with the musical accompaniment by a lone piano which simply does not do this rich score, originally orchestrated by the legendary Jonathan Tunick, any justice whatsoever. Not only was it hacked to pieces, there was far too much “cutesy” staging and abject mugging going on throughout the evening that it interfered with and detracted from the script and score. This production simply looked like there was no money and not enough people, so the company “made do” with a bargain-basement version.

It is a credit to the score by Sondheim and book by James Lapine that people were still able to enjoy it through all of the muck on stage in this production. Knowing what this show can be made me realize how much more the audience would have enjoyed it if they had seen it unencumbered by antics, musical accompaniment that didn’t often get lost, and voices that were up to the task at hand.

Let me interject here that I am probably in the minority about this although there were audience members who left during the intermission on the evening I attended. The show was extended. I have had several conversations with those who saw it after me; several of whom had never seen it before. Their responses included remarks like, “It was so imaginative,” “They really made do with very little,” and “I thought the clutter on stage was wonderful.” When I asked those who had not seen it before about specific plot points like The Mysterious Man being The Baker’s father, I was generally met with “He was? Oh, I didn’t get that.” In fact, many of them didn’t get much of the storyline, and it’s not because they are incapable of it. They, like the theatre company, lost the plot somewhere along the way.

The story, in brief, mixes together the lives of several fairytale characters: Cinderella, The Baker and His Wife (which seems to have been adapted for dramatic purposes from THUMBELINA), Jack the Giant Killer, Rapunzel, and Little Red Riding Hood. Oh, there’s a bit of Sleeping Beauty and Snow White thrown in as well. They all wish for something, and as they find out “Wishes come true, not free.” The first act has a seemingly happy ending, Jack and his mother are rich, Cinderella is marrying her Prince, The Baker and His Wife have a child, and the Witch is once again beautiful. However, that happiness is short-lived, and the second act deals with all of the repercussions of their transgressions with the few remaining characters wiser and stronger because of their ordeals.

The first problem with this production was the set. There was no sense of focus on the stage. Left and right featured floor to ceiling panels of piano sound boards, and the back of the stage was filled with ropes which one can only imagine were supposed to be piano strings. Here comes the question, folks: “Why?” Did it look like a woods? No, it looked like a series of ropes. The rest of the set consisted of unmatched tables, chairs – stuff spread about which often got in the way of the action and never helped the audience to truly establish a scene. The costumes by Whitney Locher were simply a series of rag-bag things that made it look more like MARAT/SADE than INTO THE WOODS. The witch came out particularly poorly with what looked like a black slip for a costume along with black opera gloves. The physical production could only be described as “post-apocalyptic” grunge or a badly interpreted production of GODSPELL.

Vocally, the show was weak as well. Only a few of the performers were up to the challenges of this score which requires solid singing along with extremely crisp diction. Sondheim’s lyrics are dense and contain wonderful plays on the language. For instance, Jack’s Mother sings the following about their cow Milky White (I’ll get to him in a minute):

“There are bugs on her dugs. There are flies in her eyes. There’s a lump on her rump big enough to be a hump, son. There’s no time to sit and dither while her withers wither with her”

Although Liz Hayes, who played Jack’s Mother and Cinderella’s Stepmother, was too young for the roles, she sang well and delivered and excellent performance, there were others who did not handle the music well. They included Noah Brody who mangled the Wolf’s song and his work as Cinderella’s Prince, Andy Grotelueschen who gave a weak performance as Rapunzel’s Prince, and Paul J. Coffey who just seemed out of sorts as the Mysterious Man who is eventually revealed as The Baker’s Father, and sadly, Jennifer Mudge who was simply lackluster, wanting, and sometimes apologetic as the Witch.

There were some good voices and performances in the cast, but they were up against the dire physical production. Jessie Austrian and Ben Steinfeld were both charming as The Baker’s Wife and The Baker. They showed that they understood the material and gave it its proper due. Patrick Mulryan, who is a giant himself, gave an excellent performance as Jack, and Claire Karpen was charming as Cinderella. Emily Young was wonderfully quirky as Red Riding Hood, but she did not have the proper edge to make the character fully successful.

Musically, Matt Castle worked valiantly to keep the company together with his piano playing which he had to augment to catch up or cover errors by the performers. There is just too much music in this show for it to be reduced to one piano and be successful. The addition of a few other instruments (including some really bad guitar playing) just made things more disjointed and sad.

One of the overused words I heard from the audience was “clever.” Much of what was on stage was so clever that it didn’t seem to belong to this script in the same manner as the set did not belong with what was happening.

The Wicked Stepsisters were played by Grotelueschen and Brody as they stood behind a drapery rod with the dirty drapes acting as dresses. They mugged so badly that their lines were obscured and the moment lost. Grotelueschen was also guilty of this when he played Milky White. His antics overshadowed what was being said, and he not only drew focus, he also upstaged the others who were delivering plot points. Mugging was rampant throughout the evening.

The problems here more than likely came from their being two directors who were also in the show. They truly needed someone to play referee and simply say, “NO” many times. Brody and Steinfeld are both founders and artistic directors of Fiasco Theater, and they have been responsible for many interesting productions. This is not one of them. They were out of their depth with this production of INTO THE WOODS, and were too close to the project since they were in it and controlled it. This may have worked for them in the past, but it did not work here.

INTO THE WOODS is a huge undertaking, and unlike others, I cannot get excited about “reimagining” works that are proven, especially when that reimagining means that the production will not do justice to the work, and Fiasco Theater certainly did not do justice to this work.

Absence did not make my heart grow fonder; I just got angrier and wish that all of those audience members who enjoyed what they saw would find a copy of the DVD of the original so that they could hear what the show should sound like. I’m not saying that the original production of any show is always the best, but here, it was certainly far more understandable and enjoyable.

I really wanted to like this production because I truly love this show, but it was impossible for me to do so here

Ben Brantley of THE NEW YORK TIMES wrote in his review of the show, “Never mind that this production doesn’t feature anything like the usual highly polished, highly trained vocalists and orchestra customary for the rendering of Sondheim. Onstage you’ll find one upright piano (played by Matt Castle) and a few other instruments (a cello, a guitar, some woodwinds) scattered about for cast members to pick up from time to time. And some of the performers, to be blunt, can barely carry a tune.” Perhaps Mr. Brantley can “never mind” that there are few singers or a decent production on stage for a show, but some of us who love the theatre still expect it. This production was simply far too much about process and not nearly enough about production. It was a glimpse at what happens in a workshop environment before all of the pieces are put together in a finished “whole.” There was far too much of the “Let’s throw it at the wall to see if it sticks” on view here.

Review: THE WINTER’S TALE – McCarter Theatre

April 8, 2013

In 2009, Rebecca Taichman staged a magical production of Shakespeare’s TWELFTH NIGHT at the McCarter Theatre Center in Princeton, NJ. She showed an understanding and trust of the material that made the evening glorious and telling. It is sad that that understanding and trust are not evident in her recent outing at McCarter, an unfocused, spare, and ugly production of one of Shakespeare’s lesser performed scripts, THE WINTER’S TALE which is now appearing in McCarter’s Matthew’s Theatre through April 21, 2013.

In 2009, Rebecca Taichman staged a magical production of Shakespeare’s TWELFTH NIGHT at the McCarter Theatre Center in Princeton, NJ. She showed an understanding and trust of the material that made the evening glorious and telling. It is sad that that understanding and trust are not evident in her recent outing at McCarter, an unfocused, spare, and ugly production of one of Shakespeare’s lesser performed scripts, THE WINTER’S TALE which is now appearing in McCarter’s Matthew’s Theatre through April 21, 2013.

The main problem here is that the cast has been paired down with many actors doubling and tripling roles which can become confusing even for those who know the script. Characters have disappeared and been combined which also weakens the storyline. The layers that make Shakespeare’s work so rich are all but gone here. It is a headfirst attack on the material instead of fully realized treatment of the script. Taichman has also chosen to equate the rustics with witless morons, something that is supported by the ugly costuming by David Zinn when Shakespeare simply allows them to be naïve, unschooled, and sincere in comparison to many of the royals. She has also removed the shepherdesses Dorcas and Mopsa who show that Perdita is royal just by their mere presence and actions and the comparisons that can be made between them. Many of these lost reference points also help to confuse. The lack of cast numbers also renders the “sheep shearing festival” less than festive.

The plot may be unfamiliar to many. Leontes, King of Sicilia, goes suddenly mad and believes that his wife Hermione is carrying the child of his best friend Polixenes, King of Bohemia. Although she is blameless, a fact that is supported by the Oracle of Delphi, Leontes still condemns her and proclaims that the daughter she has delivered, who is named Perdita, be taken far away and be left to the elements and wildlife. Hermione collapses, and she is taken away by a woman of the court named Paulina who returns to announce that Hermione has died. At that time, Mamillius, heir to the throne also dies of remorse because of his father’s actions. Leontes is wracked with guilt.

Perdita is taken to Bohemia by Antigonus, a member of Leontes’ court and husband to Paulina, where he is promptly eaten by a bear. Perdita is found by a shepherd and raised as his own. Sixteen years pass, and Perdita grows into a charming young woman who is different from the other girls in her village. This is noticed by Prince Florizel, son of Polixenes. Polixenes learns of this relationship, and Florizel and Perdita flee to Sicilia where it is eventually disclosed that she is Leontes’ daughter whom he welcomes with open arms. From here, there is a happy ending, and everyone ends happily except for Mamillius and Antigonus.

The evening belongs to Hannah Yelland as Hermione and Brent Carver as Camillo, a servant and advisor to Leontes. Both deliver beautifully developed and honest characters. There is no artifice in their delivery, no gimmicks or forced voices or line deliveries found in the performances of others throughout the evening. This may also be that they are two of only three actors who embody only one character in this condensed cast. The other, Sean Arbuckle who plays Polixenes also does a creditable job with a character who is there mostly to react to situations and cause change. Polixenes is essential because he must be there to cause Leontes’ mistrust and be the impetus for Florizel and Perdita to flee to Sicilia.

The staging of the piece also contributes to the confusion. Characters generally do not leave the playing area, so there is little to no change in costuming in either act, so it is often difficult to tell when an actor has become someone else. This is especially true in the first act when the staging often resembles musical chairs. When a scene ends, the cast wanders around the chairs or table in seemingly aimless circles which may expedite the evening but does nothing for clarity.

The physical production is also problematic here. Zinn’s costuming, especially the rag-bag approach to the rustics, is generally bland in the first act and garish in the second. Autolycus, who is a con-man, is dressed in a blue sateen suit with a fuchsia sequined cape – why? Also, the actor was obviously told to leave the left shirttail out of his pants for some reason as it is glaringly in the same place a costume change – why? The shepherds all look as though they dug through clothes donation bins in the dark to arrive at their costumes, and the entire effect harkens back to the bad Shakespearean productions of the 1980s. They are rustics, not derelicts.

The set by Christine Jones is also questionable. Although the two gray proscenium arches (with cabaret lighting around them – why?) are not obtrusive for the scenes in Sicilia, they certainly do not belong in the countryside of Bohemia. One may have been a frame, but the second arch is too far upstage to not be a part of the action. Also, the oval configuration of pendant lights that depict the court of Sicilia just stay there for the entire play. In order for a unit set to work, it must be a logical part of all scenes – the arches and lighting are not.

The countryside of Bohemia is denoted by green fluorescent tubes lighting the blue-gray back wall with a large billboard depicting a landscape (nicely painted) leaned against the wall. Although this is not stellar, it is moderately unobtrusive. However, the addition of huge wooden butterflies on sticks (painted only on one side and black on the other – why?) and two-dimensional freestanding sheep prints on stage are affronting. The butterflies look cumbersome, and the audience knows it is in the country and do not need the cheap indication of it.

There are other questions to be answered here as to why chairs are turned upside down and have mirrors or sky painted on their bottoms. This, like so many other choices, seems to be made simply because the idea was “This will look different.”

The only positive constant in the physical production is the lighting by Christopher Akerlind. He does attempt to make something of the uninviting space, and his lighting for the final scene is most effective.

After TWELFTH NIGHT and Taichman’s wonderfully bizarre offering of SLEEPING BEAUTY WAKES, this production of THE WINTER’S TALE is truly disappointing. There are a few good performances on stage, but the questionable cutting and staging overshadow them. I wanted to like it because I very much like this play, especially the romance offered in the second half. It has often been called a problem play because of the huge shift in its mood. I found myself moved by Yelland’s performance as well as the energies devoted to the production by the cast, many of whom who would have benefitted from less distracted direction that trusted the material.

Even with all of my complaints, it should be seen only because it is one of Shakespeare’s plays that is rarely performed in this country. However, a caveat for all who go: read a synopsis of the play before you attend. That way, you can fill in some of the gaps left by this production and not be as lost as many of those in the audience around me were. As Mamillius says shortly before he dies, “A sad tale is best for winter,” and this is certainly a sad tale.

Theatre Review: RICH GIRL at George St. Playhouse

March 16, 2013

The latest revival of the stage adaptation of Henry James’ novel WASHINGTON SQUARE titled THE HEIRESS closed on February 9, 2013 after a successful eighteen-week limited run of 117 performances that earned back its investment. The story of a young woman who is filled with self-doubt due to the machinations of a parent is timeless, and it is now receiving a fresh infusion in the George St. Playhouse / Cleveland Playhouse co-production of Victoria Stewart’s RICH GIRL which is appearing at the George St. Playhouse in New Brunswick, NJ through April 7.

Where noted physician, Dr. Sloper, belittles his daughter Catherine because she is alive and her “perfect” mother died at Catherine’s birth in the original, here money guru Eve Walker (Dee Hoty) controls and marginalizes her daughter Claudine (Crystal Finn) because she is the product of an unhappy marriage. In both stories, the young women must find their strengths themselves. However, where Catherine seems to be left in a world of darkens and solitude, there is hope for Claudine, especially for those of us who are incurable romantics and really need happy endings.

Eve is a popular financial speaker and author in the mode of Suze Ormon. She was a waitress who married a young law student, put him through school, and was then left destitute by him while eight months pregnant with Claudine. It’s no wonder then that her suggestions include ideas like, “Being in love means seeing a lawyer before you get married,” and “When a man and a woman truly love each other, they will sign a pre-nup.” She now has a multi-million dollar philanthropic organization that focuses on educating children which she intends to leave to Claudine if Claudine can manage to prove her worth to her mother.

Also, as in the original, there is a speculative love interest. Here, it is theatrical producer, director, designer, and actor Henry (Tony Roach). Where the original Morris Townsend was overtly an opportunist looking to get Catherine’s money, Henry is written with such care that the question remains entirely open-ended. Eve, however, believes that her money is all he is after since she cannot imagine why anyone would love or even want her clumsy, awkward, and backward daughter. It is clear to see that Henry is, in many ways, similar to Morris, but Henry has an obvious conscience that Morris lacks.

One final character comes into play in this mix. In the original, it’s Catherine’s widowed Aunt Lavinia who only sees a chance for Catherine to not be alone any longer. RICH GIRL has the formidable talents of Liz Larsen as Maggie, Eve’s assistant and Claudine’s guardian angel. Larsen adds a wonderfully sarcastic edge to the proceedings with hilarious readings of lines like “If you were only married, older, balding, and on the Internet, you’d be perfect for me” which Stewart has amply scattered throughout the script. There is a pleasant balance here of comedy and pathos that is not evident in the original text, and the treatment is fresh and beautifully realized.

Does Henry really love Claudine and will they be together eventually? It would be unfair of me to tell – besides, I know what I want to happen, and it may not have been Stewart’s intent.

Just about everything regarding this production is superb. The unit set by Wilson Chin is attractive and serviceable. When it comes down to people discussing minutiae such as to whether or not the sofa, coffee table, and bar set-up are right for the room (I do not think they are.) and finally deciding that Eve has money and possibly not taste, it’s a good sign that the set is stellar. One or two costumes in the otherwise excellent design by Jennifer Caprio also missed the mark such as the ugly red “sweat pants” and strangely patterned top for Claudine in the last scene. The lighting by Matthew Richards includes some absolutely stunning sunrises and sunsets, and Dave Bova deserves a special mention for the excellent wig designs for Claudine and Eve.

The ensemble on stage at George St. is extremely strong. Hoty makes Eve both a detestable and empathetic character. Where Dr. Sloper overtly loathes his daughter, Eve can’t help but see her as the product of her failure, and she does not like failure, but also as something she needs to protect and for which she must ensure a solid future. She does care, but she is so emotionally damaged that she cannot fully show it. Eve has decided that the only way she can survive is by being a harder person than everyone else. It is to Hoty’s credit that one can still care about Eve even though she seems as though she is heading towards the isolation of Dickens’ Miss Haversham in her single-mindedness. She believes she fully understands the world, and sums up Henry’s proposal of marriage to Claudine by reminding her that “I can turn on the T.V. every night of the week to watch someone eat bugs for the chance to win $25,000. That’s the world we live in.” To liken a marriage to one’s daughter as being as questionable as eating “bugs” and other such stunts for money is reprehensible.

Finn’s Claudine is a charming study in self-doubt initially, but as she becomes more self aware and sure of herself, her spine and carriage change as well, and she blossoms before the audience. Claudine could also be an unlikable character, but Finn imbues her with so many nuances and failings that one cannot help but care for her. Even when she has made the transition to successful businesswoman, there is still some of the child-like Claudine present.

Maggie acts as the Greek chorus and fills in all of the necessary talking points; this is often a thankless job on stage. Shakespeare often singled out one character like Benvolio in ROMEO AND JULIET who always got left behind to tell everyone what happened in case they were napping. Do people generally remember Benvolio when they talk about the play? No! However, people will remember Liz Larsen who is immediately recognizable as the wisecracking “Eve Arden” friend who always seems to be on the fringes but is right in the middle of everything. Here too is a character who is somewhat reprehensible. She spies on Claudine for Eve, does thorough background checks on Henry, but is still immensely loveable. Larsen also shows her impeccable timing delivering the often Simon-esque one-liners supplied to her by Stewart.

Roach has the toughest job of the evening since he works with a character who is purposefully enigmatic. Whatever choices he has made for his character’s actions must pretty much remain transparent so that the audience keeps guessing throughout. Roach is charming and energetic and, most of all, is believable. Even if he is a heel, he is still a likable heel, but he might not be a heel at all.

When all is said and done, RICH GIRL is an excellent way to spend two hours in a theatre. The well written characters are superbly acted in a visually pleasing production, and the adaptation is never forced and, for those who know the original material, more of a homage to the creations of James than a copy. It is nice to see an intelligently adapted piece that actually extends the characters, adding depth and nuances that are true to the change in time periods. Even if it does not make it to Broadway, this show is certain to be around in regional theatres for some time to come.

SPECIAL LIVE TWO-HOUR FUNDRAISING DRESS CIRCLE PROGRAM

October 4, 2012

Join us on Sunday, October 7; Ted and I will be hosting a live, two-hour DRESS CIRCLE program as the kick-off event of the current fund drive. We’ll have some interesting nostalgia recordings as well as some of our usual antics in the first hour. The second hour will be dedicated to a survey of Broadway musical over the past ten years. WWFM is celebrating 30

years on the air, and THE DRESS CIRCLE has been there for over 28. We’ll have some special offers for those of you who feel you can support THE DRESS CIRCLE and classical music by becoming a member of WWFM during these two hours. We’ll be looking for sustaining members who can afford to promise as little as $10 a month, as well as anyone who wants to help keep this wonderful station on the air. We hope you’ll join us.

Review of VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE – McCarter Theatre

September 15, 2012

For some, a simple given name can determine one’s fate, and in Christopher Durang’s new comedy VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE celebrating its world premiere at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre through October 7, everyone seems a bit trapped by those names. It isn’t necessary to know Chekhov to appreciate and enjoy this offbeat comedy, but if you do, the brilliance of Durang’s writing is even more apparent.

Vanya and Sonia have been living a secluded life in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. They stayed home to take care of their aging parents (who were academics who loved the classics – hence the names) while sister Masha went off to live her life and be a stage and film actress. Along the way, Masha made a series of films playing a nymphomaniac serial killer, enough money to pay for her parents’ final years and to keep her brother and sister, and live through five failed marriages. That’s about to come to an end. Masha is back in all her neurotic glory with a pec-popping toy-boy named Spike, and her career is in a state of flux. She does not have the money to continue to support her brother and sister, and the house might be sold. Although the basic plot may seem relatively simple and a bit mundane, the characters inhabiting it are far from that, and nothing is as simple as it seems.

Just as his namesake, Vanya (David Hyde Pierce) bemoans the failings of his life, a life lived for others. He is over fifty, gay, and living with the realization that life has passed him by. He has obviously not had a relationship of any meaning and is simply in despair.

Sonia (Kristine Nielson), who like her namesake has also lived for others and tries to rationalize her and Vanya’s lives to a point. Although she hopes that there will be something better, she doesn’t seem to sure that it will ever come. Surprisingly, she currently likens herself to a wild turkey that sleeps in a tree and falls out during the night.

Masha (Sigourney Weaver in a role that is light years away from Ripley or Grace Augustine) is a bit of a cross between the “Mashas” of THE SEAGULL and THREE SISTERS. She makes strange choices in men whom she believes to be more than they are, but she also was raised to believe she was a fabulous actress which, judging from the roles which she discusses, is not the case. This is similar to the concert pianist Masha from the three sisters. There, however, all similarities joyously end. This Masha seems to surf on the edge of reality.

Nina (Genevieve Angelson) is true to her SEAGULL alter ego because she is infatuated with the fame of Masha and wants to be an actress herself. Fortunately, her fate, as far as we know, is not the same unhappy one.

Besides Spike (Billy Magnussen) an oversexed, narcissistic young actor, another non-Chekhovian character fits right in with this bizarre group. She is the housekeeper Cassandra (Shalita Grant) who, like her Greek counterpart, suffers from bouts of premonitions that have hilarious consequences and that few believe.

The action takes place over the course of two days on a phenomenally detailed set by David Korins which is beautifully lit by Justin Townsend.

Director Nicholas Martin has chosen to keep the actors’ delivery stylistically similar to Chekhov’s syntax which is beautifully captured in the cadence of Durang’s script. This generally works well, and the disparity between the family members and the three outside characters is clear. However, some of his staging is cumbersome and extraneous involving excessive movement or the need to move furniture. This is just one of a few small issues that lessen the impact of the evening. The second act is a bit long at this point, and the cast needs to work on pacing so that lines do not get swallowed by the audience laughter of which there is a great deal. Since this is a new work, all of these should be corrected by the time that this show opens at the Mitzi Newhouse Theatre in Lincoln Center on October 25.

I don’t want to give away too much of the story because the fun here is discovering all of the glorious quirks that make these characters work. There are, however, two interesting moments in act two. Kristine Nielsen has a telephone monologue which is not only beautifully written but is gloriously performed. She is simply stunning in a quiet moment where the audience cannot help but feel overwhelming compassion for her. She externalizes the pain she has felt since being adopted into this bizarre family at the age of eight so that it is palatable. This monologue alone is “worth the price of admission.”

The other moment, although a bit long and rambling, deals with another Chekhovian theme: the pain and loss that comes with progress. Vanya has lost a great deal of connection to life, and he bemoans the fact that Spike is indicative of the loss of social mores in America in an outburst decries his desire to go back to what he believes were more innocent days when Ed Sullivan, Ozzie & Harriet, I Love Lucy, and dial telephones among other things made life better. Although wonderfully funny and telling, it goes on too long which lessens its impact. It’s still, however, a list of things that have crossed the minds of many of us “of an age” who remember a time when it wasn’t necessary to be constantly attached to the world, a time when people were a bit more conscious of others around them.

It’s wonderfully silly, and I don’t think I will ever forget the visual of Weaver dressed as Snow White or the superb Maggie Smith imitation offered up by Nielsen as the “Wicked Witch from Snow White as played by Maggie Smith on her way to the Oscars” which is the kind of thing one comes to expect from Durang’s wonderfully quirky world view.

VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE is one of those interesting shows that appears to be abject silliness initially, but once one digs through the surface artifice and manners, there are universal themes and situations that add up to much more.

Visit http://www.mccarter.org for more information about this production.

McCarter Theatre’s – PHAEDRA BACKWARDS: An Afterthought

November 18, 2011

This is a postscript. The world premier run of the show has ended, but life got in the way of me writing about it before. Perhaps it is better this way.

Let me start with this statement: The best part of the McCarter Theatre Company’s production of Marina Carr’s PHAEDRA BACKWARDS is the poster. The rest was rather flawed and confusing.

Phaedra was the daughter of Minos and Pasiphae and sister to Airadne. The myth contends that Minos upset Poseidon, so he enflamed Pasiphae with lust for a white bull with which she mated, giving birth to the Minotaur. Theseus killed the Minotaur with the help of Ariadne whom he married, but she died (in various ways according to various versions of the myth), and he married Phaedra only to live unhappily ever after.

Phaedra fell in love with Theseus’ son by a previous marriage, Hippolytus, who rejected her, and she is the ultimate cause of Hippolytus’ death by being dragged by his horses or attacked by a Kraken or a bull or a wave or a strong wind and drowned. You choose.

That’s the back story. It is good to know the backstory of the events in this play since it jumps around chronologically with characters often inhabiting the same space in different times and at different ages for no viable reason. That is one of the main problems with this script. Why was it written?

As staged, this script resembles a “white-trash” version of WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF? without any of the charm of the Albee original. Phaedra swills wine throughout and brays at anyone who comes near her. Indeed, Stephanie Roth Haberle’s Phaedra runs the emotional range from angst to angst. Neither script, approach, nor direction gave her any depth of character.

At one point, Theseus asks: “What’s the point of this?” which is a rather loaded question since I had been wondering that for some time. Besides changing the story or not giving enough information to help make certain aspects of the story make sense (such as Pasiphae’s reasons for lusting after the white bull), nothing new is developed. Here, these descendants of gods and heroes are reduced to malicious whiners, and the shifts in time and place tend to be rather confusing.

Equally confusing was a scene where Minos, Pasiphae, Ariadne, and Minotaur come back from Hades, string Phaedra up on a chain, and do something to her. I believe they were supposed to be cutting parts of her off to eat, but I cannot swear to that fact. It made no sense. Why would they hate her? Ariadne died before Phaedra married Theseus; Phaedra did not take her away. It was Ariadne who helped Theseus kill Minotaur (who, in this version, was a very friendly little calf-child), but he is not angry with Ariadne, and… Never mind. It just made no sense. If the audience was supposed to believe that this was Phaedra tormenting herself, it missed the mark.

Oh, I must admit; I did not go to the pre-show lecture which explained to any willing audience member what to look for in the show. I’m sorry; I come from a rather diverse theatrical background. If I must be told what a show means or what to look for so that I can understand it, there is something definitely wrong with the show. I know the myths surrounding these people well, and things just did not add up.

Since this is an afterthought, I won’t go into much further detail. Let it simply be said that the script and production were extremely disappointing. The performances were variable with most of the characters seemingly walking through their parts. Some, like Julio Monge as the Minotaur, were simply miscast and were not helped by poor costuming and ludicrous staging.

Once again, I was left with a resounding “Why?” echoing through my head. Why would someone do this if there was not going to be an attempt to in someway enhance or show greater depth to this story? This is especially true when one looks at Racine’s version of this myth. For sheer theatricality and emotion, it cannot be beaten.

It is sad when the dialogue in a script gives critics the perfect fodder to use against it. Some of my favorites in this included:

“You’d watch anything if it was lit properly.”

“It’ll all look better in the morning.”

“I am not equipped for this; leave my terrace.”

Minos asks: “Am I in the right place?”

Ten Cents a Dance – A Misguided Musical Revue

September 18, 2011

Enough! Director John Doyle needs to stop his intrusive, gimmicky destruction of good material. Currently, his production of Ten Cents a Dance is on stage at McCarter’s Berlind Theatre. His conceit is that performers who play a variety of instruments while performing on stage in some way enhance the performance. How? The instruments and the necessity to pick-up, carry, play, and put them down again, generally has nothing to do with the material. To many, this intrusion of instruments just appears to be a cheap way of doing a musical without an orchestra. In this piece especially, those instruments get in the way of the performance, and the result is that the proceedings appear aimless and unfocused and the integrity of the material is severely diminished if not destroyed. What he has done to some of the most iconic music of the theatre by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart is criminal.

Doyle won a Tony Award for his misdirection of Sweeney Todd on Broadway, but for some, it was a case of being dazzled by the “emperor’s new clothes.” In London, where this production of Todd began its life, it was ridiculous that Mrs. Lovett would pick up a trumpet and play as Toby sang “Not While I’m Around,” and it was equally disturbing for Anthony and Johanna to sing sweetly to each other while seated on either side of the stage with celli in their crotches. This gave new meaning to the concept of “safe sex.” Many people in the audience lost the plot, literally, as the minimal staging did nothing to support Sondheim’s often superbly dense language.

He is also guilty of a splendidly inept production of Mack and Mabel in London. Once again, a down-sized cast running around with various instruments got in the way of the staging. The action that drives the show came in second to the necessity to get somewhere else on stage to grab something to pluck, bang, or blow. There are musicals where this works, but these are shows about bands of some sort. The excellent Pump Boys and Dinettes, Cowgirls, Oil City Symphony, andSmoke on the Mountain need the instruments because they are based on stories about people playing them. They are written in as part of the script; they are not imposed where they do not belong.

This is the case with Ten Cents a Dance. Supposedly, the setting is an empty bar. It looks more like a musical instrument storeroom or the bargain basement of a large music shop. Dreary lighting by Jane Cox does not add to the necessary clutter of the set by Scott Pask. The program relates that Doyle is a story teller. It would help if the audience could possibly figure out what that story might be.

Before I go further, please let me assure you that I felt the cast was excellent, and they were committed to the material – which is superb. Malcolm Getz shows that he fully understands these songs, and he presents them well even with awkward orchestrations and unfounded thematic concepts are thrust upon them. From what I can gather, five women play “Miss Jones,” the woman he has loved and lost – maybe? I was told that they represent the “women” in his life, but they are all named Miss Jones, and they are all versions of the same woman which does not support this claim. I was also wondering, at points, if he might have been a musical mass murderer, and these were the women he had killed and hidden in a variety of double bass cases or something. If this were the case, one of the songs in the evening, the lovely “Dancing on the Ceiling” from a long forgotten musical entitled Evergreen, may have served the cause better by changing the lyrics to “She dangles overhead from the ceiling by my bed…”

In essence, the evening can be summed up as: Man plays piano, progressively aging women in rather ugly dresses descend a spiral staircase, play a variety of instruments, sing some songs, and climb back up the staircase. You fill in the story.

Joining Getz as Miss Jones 5, and I considered her to be the lead Miss Jones, is Donna McKechnie. I must say, it was a thrill to see her on stage again. She can “sparkle” just as brightly here in this train wreck as she did when I saw her in London in Can-Can or back in A Chorus Line. She is one of those people whose personality draws attention for all of the right reasons.

None of this is to diminish the other Miss Joneses as they all show good presence and talent, but it seemed obvious that some of them may have been hired because they could play a variety of instruments and not because they sang well. Some of the voices are not bad; they are just not strong or full enough to do justice to the wonderful songs here. The respective Miss Jones, from Miss Jones 1 through 4 (if this helps in any way) are: Elisa Winter, Jane Pfitsch, Jessica Tyler Wright, and Diana DiMarzio.

Since the program does not give a song list with credits as to who sings what, it is a bit difficult to give credit where it is due. All five women wear variations on the same dress by costumer Ann Hould-Ward with variations on the same red hairstyles created by Paul Huntley, so the middle three Miss Jones blended together at times. Also, why the dresses and hairstyles seemed purposefully based on 1940’s designs and are made from a fabric whose ugliness defies description begs questioning. The busy floral pattern of the material and brown/blue coloring does not read well from the back two-thirds of the house. They just look like messy blobs as several of the dresses have intricate pleating and draping which further contorts the patter. For variety, wouldn’t it have been better if it was more of a similar dress pattern but with a progressive color change that would indicate the station in life of each Miss Jones? This too would give the audience some visual variety. As it is, these dresses are just more clutter in an already cluttered set.

The songs that work the best in this scant 80 minute one-act are the songs that Doyle has allowed to simply be sung. Most of the time, the Miss Joneses wander aimlessly around stage, the piano spins for no apparent reason, or Mr. Getz takes off his coat, vest, shirt, for no apparent reason – actually, it almost appeared at one point that he was rolling up his sleeves as if to exorcise these demonic women who have come back from the grave to attack him.

I honestly believe that I had more fun making up my own storyline which, like the proceedings on stage, also had nothing to do with these thirty-plus wonderful songs than I did trying to figure out what was happening on stage…but I digress.

The songs that work best are “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” from Pal Joey and “Sing for Your Supper” from The Boys from Syracuse. Because the ladies did not have to move quickly from one side of the set to another or climb the stairs to play in some half-lit area or drape themselves over the piano to play instruments from positions that are too awkward to describe, the songs retained their integrity and were joyous reminders about just how good Rodgers and Hart were/are. Doyle has imposed his bizarre vision on these songs and no one has won. What should have been an uplifting reminder of the glory of one of America’s true original art forms is a blurry, enigmatic mess.

The movement of the women on stage also destroys the opportunity to fully appreciate Hart’s often biting and always clever lyrics. The lyrics to one of Hart’s most inspired songs in particular, “To Keep My Love Alive” from A Connecticut Yankee are almost totally lost, and the delightful “Little Girl Blue” from Jumbo is turned into a game of musical freeze-tag here. It’s all too aggravating.

All of this saddens me as I was very much looking forward to seeing this show. I have enjoyed Getz in his other shows and films, and the chance to see Donna McKechnie again is one I would not miss. I was happy to have seen them; I just wish they had been allowed to do the material as it was meant to be performed: straightforward and from the hip. There is no pretense in a Rodgers and Hart song. In this production by the misguided John Doyle, there is nothing but pretense and the resounding thud of pretentiousness masquerading as thoughtful art.

mk

Ted Writes a Letter to God

September 18, 2011

Dear God,

I need a favor – again. This time it’s not for me; it’s for someone named John Doyle. Please, please inspire him to do something with his life that does not include directing musicals. He’s the director of McCarter Theatre’s season opener, Ten Cents a Dance. I’ve seen three other musicals he directed, and all of them have left me feeling disappointed . No, that word isn’t strong enough. Let’s try outraged.

I know that you’ve already blessed him with supreme self-confidence and a monumental ego. He’d need those to put himself and his concepts ahead of the obvious and established talents of Stephen Sondheim, Jerry Herman, and now Rodgers and Hart.

I wonder if he’s ever really listened to the wondrous creations that Rodgers and Hart offered us, sometimes as long ago as eight decades. So many of those lovely ballads, like the title song, look into the human heart and see regret, resignation, hope and joy in the most simple and direct ways imaginable. Those songs have stood the test of time and, hopefully, will survive the disrespect and trivialization his concept and this show have subjected them to. He squandered or misused the talents of six fine performers who wandered the stage aimlessly, rushing about to pick up and discard various musical instruments to no purpose I could fathom.

I know that some people see novelty as automatically better than tradition. I sometimes do, and I have the feeling that You do as well. Mr. Doyle has awards and a sheaf of good reviews, so it must be a matter of taste. You could give him some of that too as long as it’s closer to mine. Or Sondheim’s. Or Herman’s. Or, especially and regretfully, Rodgers and Hart’s.